Throughout history, art has been used numerous times as a tool to persuade society, as seen in political propaganda across different political regimes. Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, once stated in a speech “Propaganda works best when those who are being manipulated are confident, they are acting on their own free will,” highlighting how the Nazi regime weaponized art, literature and film to control public opinion and reinforce the Nazi ideology. However, art has also been used as an act of defiance. In Nazi Germany, countercultural artists resisted state-sponsored propaganda by exposing the true realities they faced under fascism, preserving their suppressed narratives, and challenging the regime’s control over culture. This pattern of artistic resistance in Nazi Germany contributes to the wider historical tradition in which art serves both as a means of control and a form of counterculture.

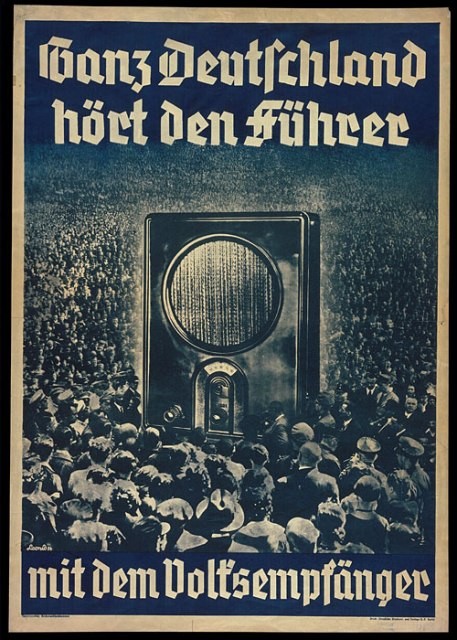

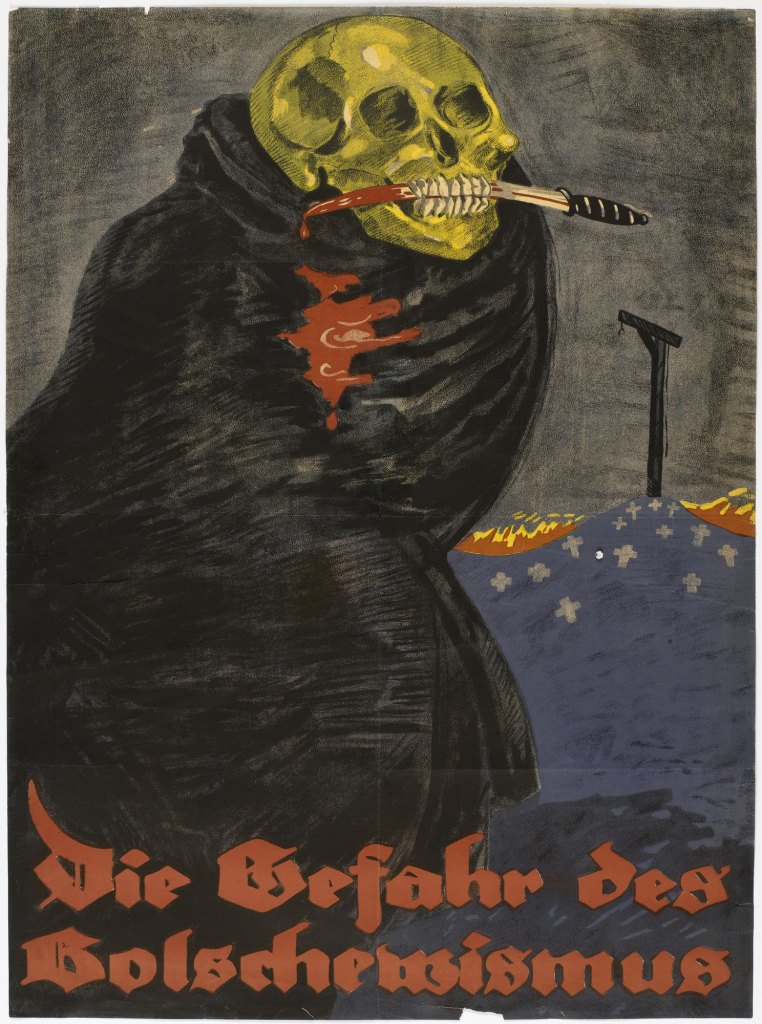

The Nazi’s used propaganda to promote Aryan supremacy, nationalism, militarism, and antisemitism. The messages were spread through newspapers, radio shows, sporting events like the Olympics, songs, art, theatre, and television (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). Once Hitler came into power, he created the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, to shape the behavior and opinion of the German public. Joseph Goebbels, who joined the Nazi party in 1924, played a crucial part to the Nazi’s use of propaganda to increase their appeal. Goebbels shared power over the press with the head of the Reich Press Chamber, Max Amann, Adolf Ziegler head of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, and eventually with Otto Dietrich, head of the Reich Press office (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). The propaganda was dark, sometimes ominous and very dramatic. Jews were portrayed as untrustworthy, greedy, scruffy, overweight, and evil, while on the other hand Hitler and Germans were portrayed as beautiful, defenders, strong, and pure. Nazi propaganda often portrayed Jews as engaged in a conspiracy to provoke war and take over the world. In addition, themes linking Soviet Communism to European Jewry, presented Germany as the defender of “Western” culture against the “Judeo-Bolshevik threat” and painting an apocalyptic picture of what would happen if the Soviets won the war. (Goggin 89).

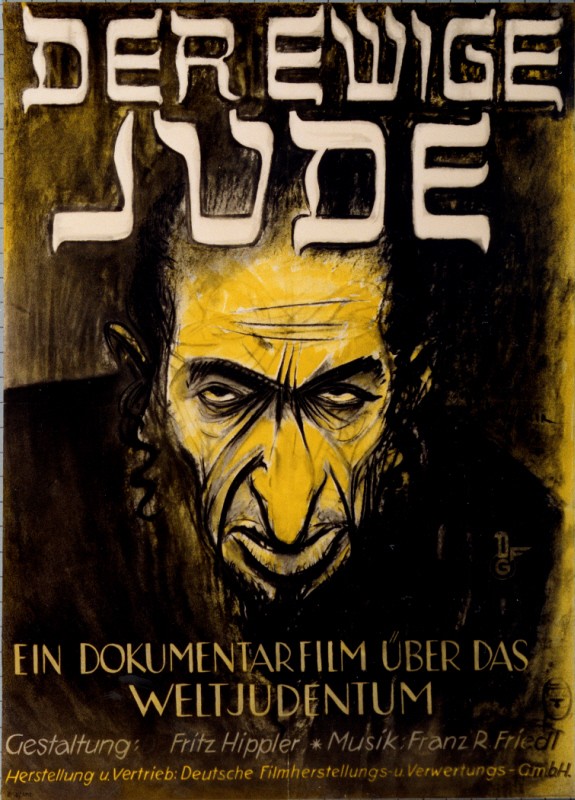

Hitler, who was an artist himself during his youth in Austria, recognized that art needed to play a major role in the building of his ideal German nation. He expressed that true German art, “must be national, not international; it must be comprehensible to the people; it must not be a passing fad but strive to be eternal; it must be positive, not critical of society; it must be elevating, represent the good, the beautiful, and the healthy” (Goggin 84). The most popular subjects in German art were peasants and artisans engaging in labor. Paintings of mothers were significant because they represented the future of the “Aryan race”, Landscapes represented the “fatherland”, in addition women’s nudes symbolized the beauty of healthy bodies, and soldiers and workers were painted to represent “heroism” (Goggin 85). Nazi films portrayed Jews as “subhuman” creatures infiltrating Aryan society. For example, “The Eternal Jew” directed by Fritz Hippler, portrayed Jews as wandering cultural parasites, consumed by sex and money. The National Socialists claimed, “Because modern artists considered everything suitable as a subject of art, “the beautiful, the heroic and the pure” were put on the same level as “the ugly, the base and the erotic”, resulting in amoral art. The National Socialists considered “race and homeland” or Blut und Boden (blood and soil) the base of a Germanic art that would express the true spiritual values of the Aryan race, purified of all Bolshevist and Semitic influences (Goggin 86). Hitler and the National Socialists made modern art as a symbol of corruption and degeneracy. According to the Nazi’s, “modern art was going to weaken German society with “cultural Bolshevism”. Only criminal minds could be capable of creating such so called harmful art. They used the term to suggest that the artists’ mental, physical, and moral capacities must be in decay. At the time, “degenerate” was widely used to describe criminality, immorality, and physical and mental disabilities.” (United States Holocaust Memorial).

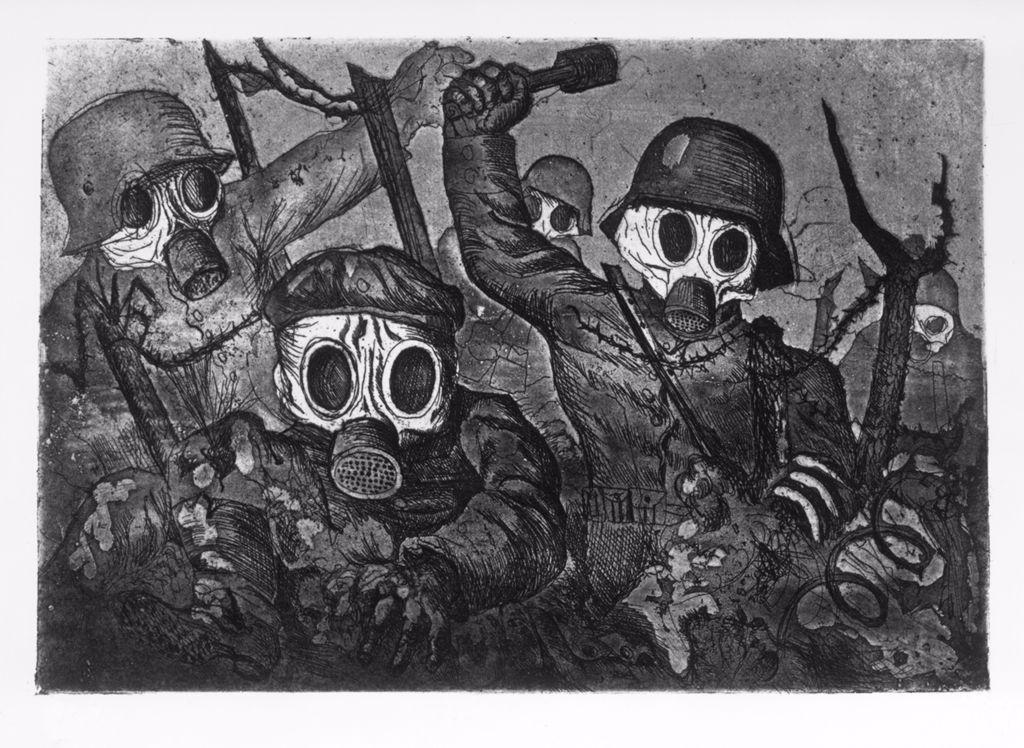

There were multiple art movements that resisted and critiqued the Nazi regime. Movements such as Dadaism and Expressionism will be the focus here. German Expressionism was the art movement that put an emphasis on expressing one’s inner experiences, feelings, and spiritual themes instead of the reality of people, nature and society (Smith 46). Expressionism can be considered the opposite of Realism. Realism was favored by the Nazi’s to promote their ideas and messages of Aryan strength and unity. Artists associated with this movement include Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann (although Beckmann rejected the label of Expressionist), used bold, twisted imagery to reveal the trauma, war, poverty and oppression. These subjects were directly against the Nazi ideals. Additionally, Dadaism was a response to the extremes of war and fascism, containing elements of satire, often rejecting logic, order and the traditional aesthetics that were inspired from Greek, Roman and Medieval art. Artists like Hanna Höch, Raoul Hausmann, and Max Ernst used painting, printmaking and satire to criticize fascism, nationalism, and Nazi propaganda. Both movements gave influential, countercultural challenges to the Nazi’s ideologies by using art to rebel and tell the truth.

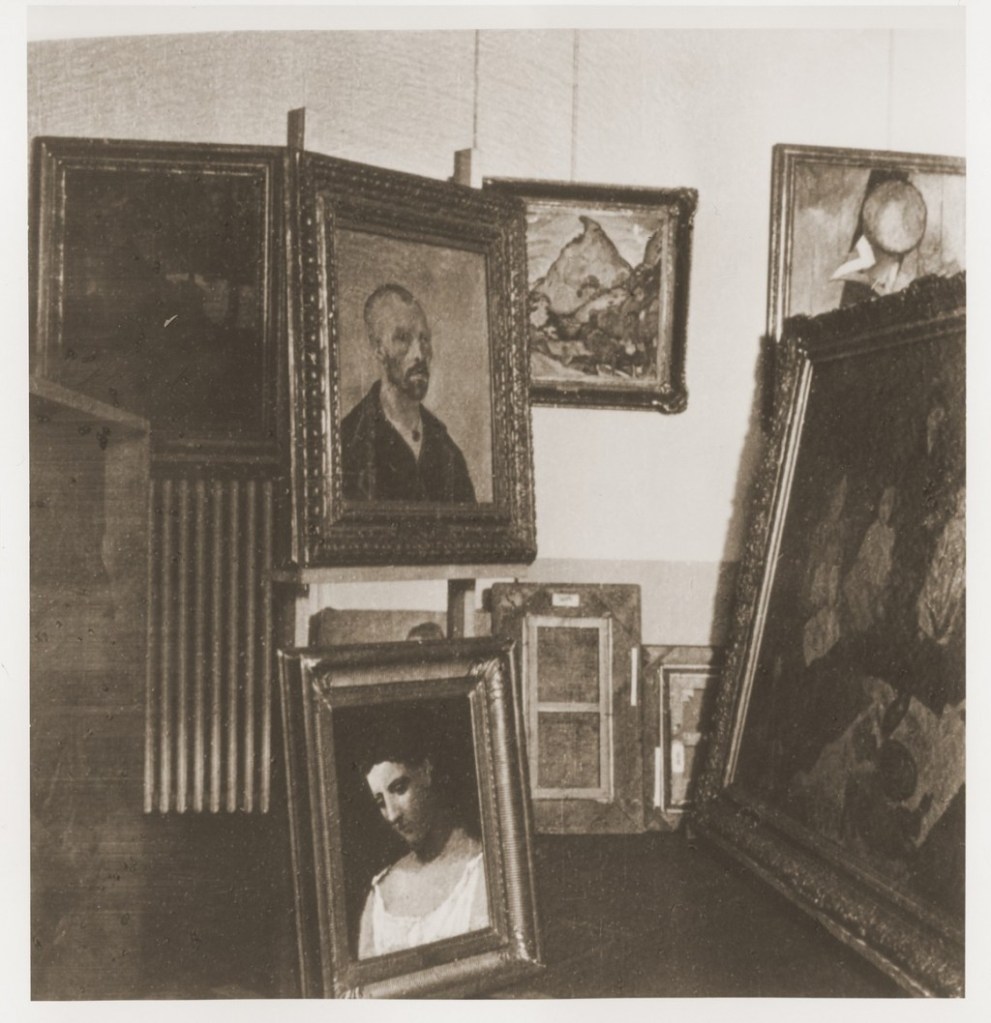

Source: The Museum of Modern Art “German Expressionism Collection”

The Nazi’s didn’t just slander and harshly criticize modern art and artists, they also confiscated art from museums and other collections. Artists were also expelled from their teaching positions. In addition, many artists like Paul Klee, George Grosz, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, and left the country (Goggin 89). George Grosz decided to leave Germany permanently for America in January of 1933. He secured a teaching position at the Art Students League in New York the year prior to him fleeing. During his exile he published a portfolio of work titled “Interregnum” which was a response to the news of anarchist and playwright Erich Müsham’s, death which was staged as a suicide. The portfolio is introduced by an essay written by the anti-Stalinist novelist John Dos Passos. In the essay, Passos boasts about Grosz’s work being “a great satirical social critic but also that of a formally radical modernist, who compelled viewers to reorganize their perception of the world and to think freshly” (Van Dyke 141). He also states, “Grosz’s work combined a visual razor edge with a bitter satirical intensity that few complacencies can survive” (Van Dyke 141). George Grosz firmly believed that Communism and Nazism were two halves of the same totalitarian coin. Through his drawings he hinted that torture in Nazi Germany was not only a way to gain information, but also an expression of perverted sexual desires (Van Dyke 142). Identically, Max Beckmann resigned from his teaching position at Frankfurt due to the actions of the Nazi regime in 1932. It was then he began working on the Departure. This work of art was a reaction to the rise of the Nazi regime. Beckmann once referred to the Departure as an expression of mystical redemption: “Departure, yes departure, from the illusions of life toward the essential realities that lie hidden beyond” (Kessler 207 and 217). Not to mention Charolette Salomon who worked in isolation while she hid in the South of France between 1940-1942. During her time in isolation, she created “Life? or Theater? A Song Play” which was a chimeric artwork that combined word, image, and music. She created approximately 1,325 pages of paintings and drawings of image and text. Her work is an extended response on the attack of modern art by the Nazi regime and a rejection of the Nazi meaning and heritage of German art and music. “Life? or Theater?” portrays Salomon’s family legacy of suicide and mental illness while also portraying the external pressure of war, National Socialism, and exile. (Freedman 4,5, and 16).

Hitler and the National Socialists made it very clear that the great names of modern German art were enemies of the German people. The nazi regime responded to countercultural art with censorship, public mockery, and condemnation. Hitler, Goebbels, and other members of the Reich Chamber of Culture, declared modern art to be “degenerate”, insisting that they were products of “racially valueless” individuals who threatened the cultural health of German society. On May 10, 1933, the Nazi’s and the German Student Association held a series of book burnings. The Nazi’s held their book burning in the plaza that was near the Opera in Berlin, where they burned 20,000 books, majority of them were stolen from Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science and the library of the University of Berlin (Rabinbach 446). Books by Bertolt Brecht, Lion Feuchtwanger, Ernst Toller, and Franz Werfel were burned. In October 1936, the contemporary art galleries of the National Gallery in Berlin were shut, and the artworks they had contained were sold abroad or destroyed. Additionally, Joseph Goebbels banned any type of criticism on art. He published a statement originally published as “Order of the Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda” Goebbels stated “I am finally and definitively placing a ban on the pursuit of art criticism in its present form. The previous art criticism, has perverted the concept of “criticism” into a sort of artistic judiciary empire, shall henceforth be replaced by the “art report”; the arts editor will take the place of the art critic (Rabinbach and Gilman 492). The following year in July 1937, the “Degenerate Art Exhibition” was opened. The exhibit contained 650 artworks from 32 different German museums. Majority of the people who attended the exhibit went for the horror of it, there was a small minority, like publisher Richard Piper, who knew they were witnessing a cultural outrage (Rabinbach and Gilman 484). As Rabinbach and Gilman note, “Nazi propaganda did not simply seek to suppress modernist tendencies; it aimed to humiliate them sand frame them as moral and national threats” (Rabinbach and Gilman 513). According to Freedman, “Will Baumeister, whose work was on display, visited at least twice. He bought postcards and a catalogue at the Great German Art Exhibition, only to turn them into examples of decadent art by drawing on their surfaces in a playful, surreal style that subverted their conservative representations of neo-classical heroism” (Freedman 6). Equally important, the Great German Art Exhibit opened at the House of German Art in July 1937. 600 works of had been shown out of the 16,000 thousand that were submitted. The exhibit showcased monumental sculptures that glorifies the German body, the paintings portrayed the relationship between the German peasant and the land, the bravery of the German soldier, and the beauty of the German landscape. The exhibit included works by Arno Breker, Fritz Erler, Ferdinand Spiegel, Josef Thorak, Adolf Ziegler and Ivo Saliger. Hitler admired Ziegler’s work so much, he purchased a few of his works to add to his personal art collection.

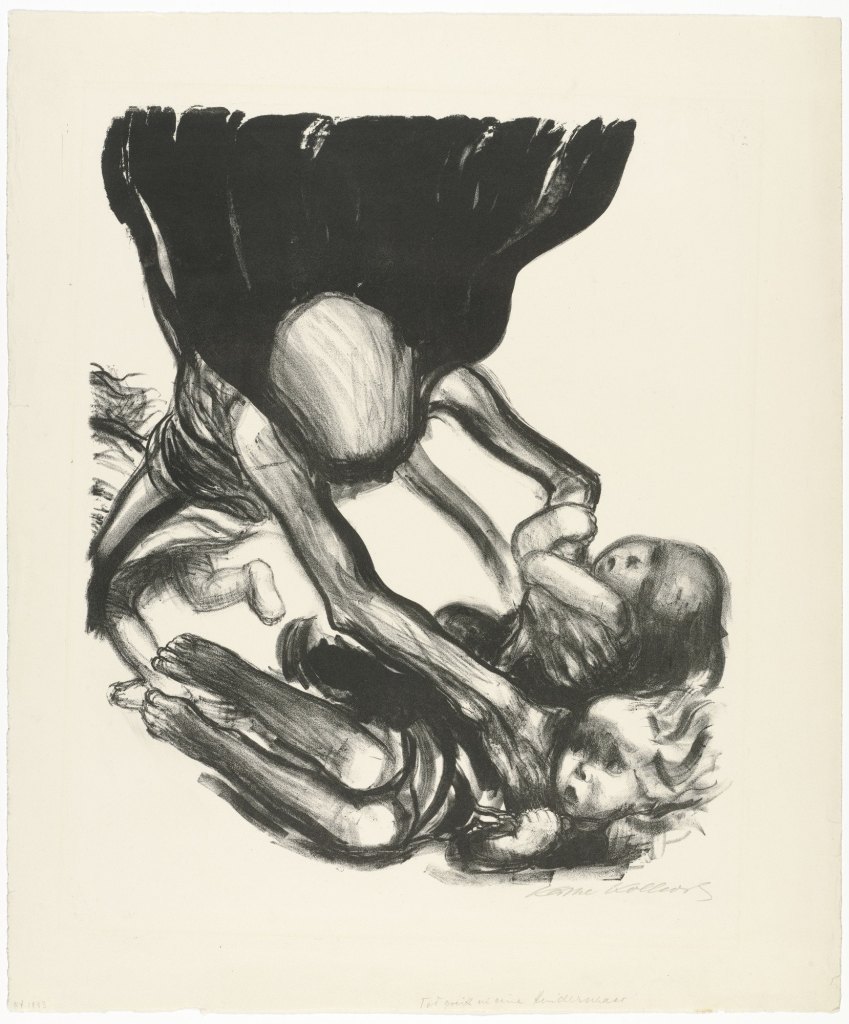

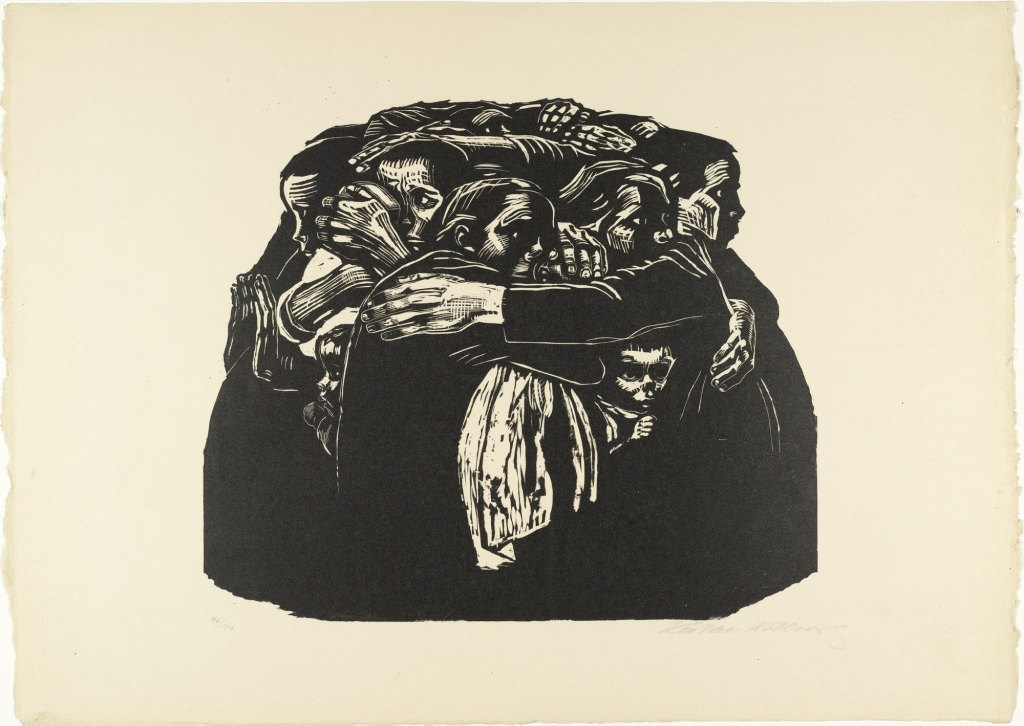

Again, Nazi art focused on portraying themes of racial purity, traditional general roles and families, and nationalism. Käthe Kollwitz used her art to expose the brutality and lack of morality of such beliefs that the Nazi’s enforced and held. Kollwitz’s work was empathetic and human-centered, providing an alternative perspective of society that focused on the suffering of the oppressed rather than glorifying the ideals of the Nazi supremacy and militarism. Death was a constant theme in Kollwitz’s work. In fact, she created an entire portfolio focused on the theme. Ten years before Kollwitz completed the portfolio she wrote in her diary “I must do the prints on Death. Must, must, must” (The Museum of Modern Art). In the portfolio, Kollwitz portrayed mothers mourning, widows grieving, and poverty-stricken children suffering as the result of WW1 and the Nazi regime (Petropoulos 44). Her art showcased her rejection of male dominance and the Nazi glorification of war. Instead, she highlighted the emotional and mental toll of violence on women and families. Similarly, Max Beckmann also produced a body of work that critiqued postwar politics and German society. He created a symbolic and distorted series of work titled Hell, in which he portrayed the suffering and inhumanity of Berlin post WWI, these works included scenes of cruelty and distorted bodies. As Wendy Weitman notes, the portfolio “harshly illustrates man’s inhumanity to man,” and Beckmann’s prints feature “ironic contrasts” and scenes that evoke the trauma of war and the loss of moral direction in Germany (Weitman 18). These artists utilized expressionism, realism and symbolism to expose the true psychological and social damage created by nationalism, misogyny, and racial purity ideologies. For example, Beckmann stated that his aim was “to make the invisible visible through reality,” a mission that stood in contrast to the propaganda art that was endorsed by the Third Reich. (Weitman 18).

There was a heavy censorship put on countercultural art; this censorship had an unsettling effect on internal resistance in Nazi Germany. Some artists tried to quietly critique the Nazi regime, the threat of censorship or punishment made it risky for artists to make their critiques openly. However, in places like New York, Paris and London, countercultural German art, specifically art created by exiled artists, was seen as a bold act of defiance. According to The Third Reich Sourcebook, “Exiled artists became the embodiment of spiritual and cultural resistance in the eyes of foreign audiences” (Rabinbach and Gilman 519). Their art helped to persuade public opinion by showing the oppression happening in Germany and emphasizing the lack of morality of the Nazi state. The Museum of Modern Art featured artwork from artists like Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Paul Klee. This helped American audiences understand how the Nazi regime was suppressing freedom of expression and condemning artists based on ideology. The Museum of Modern Art portrayed banned German art as humanistic and heroic. Weitman states, “The very art that Hitler condemned and deemed as corrupt has found refuge in a free society and now speaks more powerfully than ever before” (Weitman 19). Additionally, the book burnings that took place in 1933 sparked an immediate response from America. The book burnings made America realize just how dangerous fascism was and instantly took to the streets to protest the Nazi’s cultural censorship. In addition to rallying in the streets of New York City, American libraries, colleges, and publishers planned public readings of banned books, proving that books can be used as tools of resistance. The efforts helped “to transform the victims of Nazism into symbols of cultural heroism” and set books and art as weapons of morality during the fight against fascism (Friedman 4). American newspapers disapproved of the book burnings calling the actions of the German students “ineffective”, “senseless,” or “infantile”. Ludwig Lewisohn of The Nation predicted the beginning of a “dark age,” an “insane” assault “against the life of the mind, intellectual values, and the rights of the human spirit”. Even Hellen Keller spoke out, writing an open letter in protest. In the letter she warns the German people that the burning of books could not eradicate ideas. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

Art left a major mark in long-term resistance to Nazism by preserving memories, exposing brutal truths, and assisting in the cultural reeducation of Germany after World War II. Although countercultural art was heavily censored during the regime, many works survived and regained power after World War II. For example, Freedman states, “Mary Lowenthal Felstiner’s ambitious biography To Paint Her Life: Charlotte Salomon in the Nazi Era (1994) brought Salomon’s work to a new generation of both critics and artists, and Griselda Pollock’s numerous publications and lectures on Salomon over the last dozen years served to cement her critical reputation” (Freedman 4). In addition, there was the publication of The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror, created by Willi Münzenburg and other exiled communists in Paris. In the book, Münzenburg accuses the Nazi’s of arranging the Reichstag fire for to establish more power on the eve of the March 1933 elections (Rabinbach and Gilman 841). This book alongside other attempts, laid the groundwork for understanding the Nazi regime abroad, providing evidence of the Nazi’s lies and violence. This was important in confronting German society with the true reality of the Nazi crimes.

The main lesson we learn from seeing art playing a role in resisting Nazi propaganda is that culture and creativity can be used as powerful tools of defiance, after all, art is about sending a message. Art will always remain a medium in times of extreme political tyranny, it preserves the truth and gives a voice to the opposition. Hitler knew how crucial art would be to his rise in power and with the help of the Nazi regime, weaponized art to shape public opinion but countercultural artists fought back via visual satire, underground theater, and more. However countercultural artists like George Grosz, Max Beckmann, and others, responded to Nazi propaganda with their own forms of visual and literary protest. Willi Münzenberg’s Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror used writing and visuals to expose the Nazi crimes and became an international symbol of resistance, it was translated to over 24 languages and had 55 editions published (Rabinbach and Gilman 841). His work is proof that art can break through propaganda voicing both domestic and internation opposing opinions. Today, artists continue to challenge censorship and authoritarian control worldwide.

In conclusion, the countercultural art created against Nazi propaganda and Hitler’s rise is proof that creative expression can be a powerful tool of control and in resisting oppression. Although the Nazi regime used visual and literary media to manipulate and promote racial purity, militarism, antisemitism, and ideological conformity, there were a variety of artists across Europe and even in America, who refused to let their voices be silenced. Käthe Kollwitz and Max Beckmann exposed fascism via a variety of deeply emotional artworks. Kollwitz used her work to depict death, grief, and a mother’s strength putting an emphasis on suffering compared to Nazi artwork that put an emphasis on heroism, thus challenging the regime’s worship of war and the idealized (more like sexist) female role as child-bearer for the Reich. Wendy Weitman notes that Beckmann’s prints “harshly illustrate man’s inhumanity to man” and bring “the invisible’ horrors of fascism into visibility through artistic realism (Weitman 18). These artists and their work is a reminder that in any society, culture is never one-sided.